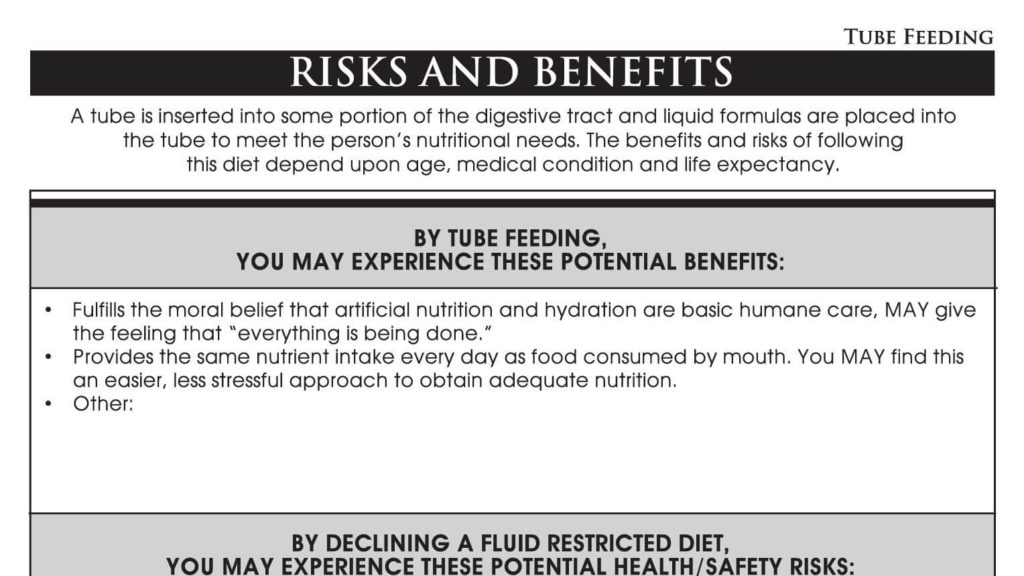

Weighing the Risks and Benefits of Tube Feeding

To some, tube feeding fulfills the moral belief that artificial nutrition and hydration are basic humane care, and may give the feeling that “everything is being done.” They say tube feeding is an easier, less stressful approach to maintaining adequate nutrition for people with swallowing issues and complications. But how do these potential benefits stack up against the potential risks associated with tube feeding?

Myth #1: Many people think feeding tubes keep people nourished and hydrated, cut down on hunger and make a person feel comfortable, but this isn’t always the case. Contrary to popular belief, tube feeding does not ensure a person’s comfort or reduce suffering. In fact, it may cause fluid overload, diarrhea, abdominal pain, and local complications.

Myth #2: Others believe that feeding tubes can prevent saliva, food or liquid supplements from traveling into the lungs that can lead to aspiration pneumonia. However, that belief is contradicted by the current evidence such as:

- Feeding tubes have not been shown to reduce the risk of aspiration or prolong survival in residents with end stage dementia.

- Oral secretions and/or gastric content are often the source of aspiration pneumonia or pneumonitis and thus will not be resolved with the placement of a tube. Saliva or tube feeding formula can travel into the lungs, especially if the person is lying down.

- Withholding or minimizing hydration can have the desirable effect of reducing disturbing oral and bronchial secretions, and reduced cough from diminished pulmonary congestion.

Myth #3: A common belief is that tube feeding helps maintain a person’s weight. Most people on feeding tubes are gravely ill, many suffering from advanced dementia. Studies have shown that such people show little improvement in weight gain. And when there is weight gain, it does not result in any improvement in their clinical outcomes.

One of the things to consider when examining the possibilities of tube feeding is how enteral feeding limits a person’s interactions with other people. This lack of socialization can lead to feelings of isolation and depression.

Another side effect of tube feeding is that it robs a person of the many pleasures that come with eating. I’m not simply talking about the taste of favorite foods. I’m talking about how our personal comfort foods can trigger happy memories of times spent with friends and family around the dinner table, at a favorite restaurant, or on a picnic. Food is linked with feelings and memories. That’s why people should be offered an informed choice about what they eat or don’t eat.

“A decision to use a feeding tube has a major impact on a resident and his or her quality of life. It is important that any decision regarding the use of a feeding tube be based on the resident’s clinical condition and wishes as well as applicable federal and state laws and regulations for decision making about life-sustaining treatments.”- CMS Letter (S&C) 9/27/2012 Feeding Tubes

Now let’s look at tube feeding and the ramifications of it for individuals with advanced dementia.

Recently, the American Medical Directors Association gathered a workgroup together and found that the number one thing that most physicians, health care professionals and people in long term care should question is whether to insert feeding tubes into individuals with advanced dementia. Solid evidence exists that artificial nutrition does not prolong life or improve individualized care in people with advanced dementia. In fact, people who are not eating due to extensive functional decline and recurring or progressive illnesses are not likely to see any significant or long-term benefit from artificial nutrition. 4-9 Their advice was to NOT insert feeding tubes in people with advanced dementia.

Think about what happens when a person becomes confused or agitated and pulls the tubing out that has been inserted and anchored into their stomach. As you might imagine, this creates a cascade of problems.

Feeding tubes have not been shown to reduce the risk of aspiration or prolong survival in people with end stage dementia. To get people with advanced dementia the nutrition they need, it is important that care partners form a relationship with the person he or she is caring for.

The Moral Dilemma

If someone’s 88-year-old mother gets deathly ill, she might go downhill fast when it comes to eating and drinking. Family members may fear that she will slowly starve to death if she doesn’t get a feeding tube. But what family members need to understand is that when a loved one has a terminal illness, a feeding tube is not going to help that person get well. As the body starts to physically decline, it shuts down vital systems so that the person doesn’t feel hungry or thirsty. Inserting a feeding tube at this critical time can actually do more harm than good because it can interfere with a peaceful and natural death. People need to understand that when the time comes, a terminally ill person stops eating and drinking and this cessation is a natural part of the dying process.

What Can Long-Term Care Partners Do to Resolve this Dilemma?

The American Geriatrics Society states that it is the responsibility of all long-term care partners to understand any previously expressed wishes of a person in their care (through a review of advance directives and with surrogate caregivers) regarding tube feeding and to put those wishes into that person’s care plan. Institutions such as hospitals, nursing homes, and other care settings should encourage choice, endorse shared and informed decision-making, and honor preferences regarding tube feeding. To address these types of issues while a person still has their mental faculties intact is the smart thing to do.

Tube feeding may be clinically appropriate in certain circumstances, but it should not be an automatic next step when other feeding strategies have failed. Before deciding to initiate tube feeding, the interdisciplinary care team should meet with the patient and family to carefully consider the risks and benefits of tube feeding and the patient’s preferences.” – AMDA Clinical Practice Guideline for Alteration in Nutritional Status, 2010

To assist you in having these important discussions with your residents and their families, we have a tip sheet that discusses the risks and benefits of tube feeding.

Planning in advance is always a good idea and really, imperative, when it comes to person-directed living. Discuss with residents and family members the concept of ‘advanced care planning’. To help you to do that, here are a few definitions.

Advance Care Planning: Making decisions about the care a person would want to receive if he or she becomes unable to speak for his or her self. These are their decisions to make, regardless of what a person chooses for their care, and are based on their personal values, preferences, and discussions with their loved ones.

Advanced Directives for Care Planning: Written documents that help to direct care when a person becomes incompetent to make his or her own decisions.

A Living Will: A living will document is a person’s wishes concerning medical treatments at the end of life, in the event they are unable to make those decisions.

Before a living will can guide medical decision-making, two physicians must certify:

- The person is unable to make medical decisions

- The person is in the medical condition specified in the state’s living will law (such as “terminal illness” or “permanent unconsciousness”)

- Other requirements also may apply, depending upon the state.

Durable Power of Attorney for Health Care (DPAHC): This document allows a person to appoint another person they trust as their healthcare agent (or surrogate decision maker), who is authorized to make medical decisions on his or her behalf. Before a medical power of attorney goes into effect a person’s physician must conclude that that person is unable to make their own medical decisions. In addition:

- If a person regains the ability to make decisions, the agent cannot continue to act on the person’s behalf.

- Many states have additional requirements that apply only to decisions about life-sustaining medical treatments.

- For example, before your agent can refuse a life-sustaining treatment on your behalf, a second physician may have to confirm your doctor’s assessment that you are incapable of making treatment decisions.

These documents provide a physician with information about a resident’s values and desires for the treatment he or she would like.

So, is there a right or wrong decision when it comes to tube feeding? No. There is only what a person thinks is the best for him or her. It is up to the professionals to present the risks and benefits of tube feeding to help make an informed choice.

- Casarett D, Kapo J, Kaplan A. Appropriate Use of Artificial Nutrition and Hydration‐Fundamental Principles and Recommendations. New England Journal of Medicine 2005.

- Leible and Wayne, The Role of the Physician Order, paper written for CHII 2010.

- Practice Paper of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Ethical and Legal Issues of Feeding and Hydration 2013

- Mitchell SL, Kiely DK, Lipsitz LA. “Does Artificial Enteral Nutrition Prolong the Survival of Institutionalized Elders with Chewing and Swallowing Problems?” J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 1998; 53:M207.

- Meier DE, Ahronheim JC, Morris J, et al. “High Short-Term Mortality in Hospitalized Patients with Advanced Dementia: Lack of Benefit of Tube Feeding.” Arch Intern Med 2001; 161:594.

- Murphy LM, Lipman TO. “Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy Does Not Prolong Survival in Patients with Dementia.” Arch Intern Med 2003; 163:1351

- Gillick MR. Rethinking the Role of Tube Feeding in Patients with Advanced Dementia. New England Journal of Medicine 2000; 342:206

- AMDA Clinical Practice Guideline: Altered Nutritional Status in the Long-Term Care Setting, 2010, 35p.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; State Operations Manual Appendix PP 483.25(j) Hydration

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; State Operations Manual Appendix PP F327 483.25(j)34.